Horror’s surrealist and realist nature provides an audience with a source of entertainment. It also grants access for Young Adults (the main audience of the genre) to explore their fears safely. However, horror wasn’t always this way. So, let’s explore the interesting tale of the birth and growth of horror…

From ancient mythology and folklore to polytheistic religion and cultural zeitgeist, all are fascinated by the fundamental element of horror: the nature of death, ‘the multiple ways in which it can occur, and the untimely nature of its occurrence’. Death is the ultimate fear of the unknown as no matter what after-life you chose to believe in, faith can only suggest so much. Death is the one thing even science cannot defy. This lack of acceptance towards death within society means ‘the place of the living is haunted by the dead’ hence, why ghost stories are so compelling. This feature of the genre is what makes horror so omnipresent throughout history as ‘societies are constantly having to address the things which threaten the maintenance of life and its defining practices’.

In the Megalithic period, horror was originally used in folklore as a cautionary tale to children for misbehaving. Stories symbolised ‘the aspirations, needs, dreams and wishes of the people’, which reinforced the status quo, established the normality of the era or confronted societal conventions of the time. To this day, that is a crucial purpose in horror: to be ‘socially, politically and culturally transgressive and challenging’.

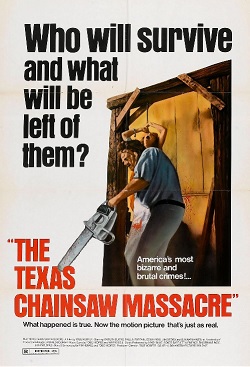

Monsters and ghouls are often used as manifestations of social fears. For example, Jekyll and Hyde explored the fear that even good people have evil inside them. Likewise, serial killers like Ted Bundy and Charles Manson in 1970s America brought a message of ‘living in fear’ to their society. As a result, horror films in the 70s starred crazed killers. Therefore, the nature of horror is paradoxical.

Horror is ‘a construction, projection and representation’ with meaning rooted in every angle of its subject. Hence, the genre ‘acts as a vehicle for us to face up to and face down what we avoid, repress, ignore or can see no escape from’ by exploring politics, religion, sex and repression.

‘Religion is not nice; it has been responsible for more death and suffering than any other human activity’ which is why it so often appears in horror fiction as it adds danger to a narrative. Horror thrives on subverting religious good which is why there’s an argument that horror may be an organised religion. As horror explores mortality and what happens after death in the same way Christianity does. This is a reason why people are drawn to the horror genre. It is not afraid to do the outrageous and be a symbol for the unthinkable.

Horror’s foundation is the ability to stimulate an emotional state in the reader. It’s in the genre’s nature to take something normal and twist it. Sex in the genre is no longer loving or passionate, it’s horrific – it’s rape or it’s assault. Metaphors in the genre are ‘built upon the idea of a hidden, silent and repressed sexuality’. In Dracula, for instance, biting his victims could be a metaphor for reproduction. Furthermore, Dracula ‘overturns the sexual politics of the bourgeois home’ by attacking women betrothed/married. Whilst “Dollies” by Kathryn Ptacek follows the rape of an adolescent girl which could stem back to the Victorian era’s twisted approach to sex with children.

Even in the literature that is not categorised as horror, the plots involve monsters that implement arousal in the reader. Shakespeare had witches; Rowling had dementors, and Tolkien had all kinds of creatures like orcs and trolls.

That is the true nature of horror.

It has been everywhere, it is everywhere and it will go everywhere. Just like our ancestors, we must too be the people that are ‘the carriers and transformers of the tales’, for as long as society lives.

WORD COUNT: (exc. Quotes) 525

Bibliography (in order of use)

Wells, Paul. The Horror Genre: From Beelzebub to Blair Witch, (London: Wallflower, 2000) page 10

Dorman, Rushton M. The origin of primitive superstitions, (London: J.B.Lippincott & Co. 1881) page 19

Wells, Paul. The Horror Genre: From Beelzebub to Blair Witch, (London: Wallflower, 2000) page 10

Zipes, Jack. Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales, (New York: Routledge, 1992) page 5

Wisker, Gina. Horror Fiction: An Introduction, (New York: Continuum, 2005) page 10

Stevenson, Robert L. Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (London: Longman, 1886)

Bergeron, Ryan. Notorious killers of the 1970s, edition.cnn.com, 2018 https://edition.cnn.com/2015/07/08/entertainment/the-seventies-the-decades-worst-killers/index.html Accessed: 01st April 2020

Wisker, Gina. Horror Fiction: An Introduction, (New York: Continuum, 2005) page 5

Wisker, Gina. Horror Fiction: An Introduction, (New York: Continuum, 2005) page 10

Smith, Jonathon Z., ‘The Devil in Mr. Jones’, Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown (USA: University of Chicago Press, 1982) page 110

Mitchell, Kate, History and Cultural Memory in Neo-Victorian Fiction (UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010) page 45 – 46

Stoker, Bram. Dracula, London: Penguin Classics, 2003

Jancovich, Mark. Horror (London: Batsford Ltd, 1992) page 50

Ptacek, Kathryn “Dollies” in New Fears, edited by Mark Morris, Titan Books, London, 2017 (page 29)

Zipes, Jack. Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales, (New York: Routledge, 1992) page 5